| Published: Date: Updated: Author: |

The Bahamas Investor Magazine July 1, 2013 July 1, 2013 Steve Cotterill |

Despite sustained pressure from alternative energy lobbyists, the global thirst for oil is showing no signs of abating. An industry worth hundreds of billions of dollars, oil discovery and production has determined the course of economies around the world from the first day it was used to drive an engine. With the recent decision to allow exploratory offshore drilling in Bahamian waters, the jurisdiction could now be poised to embrace an era of oil fuelled prosperity.

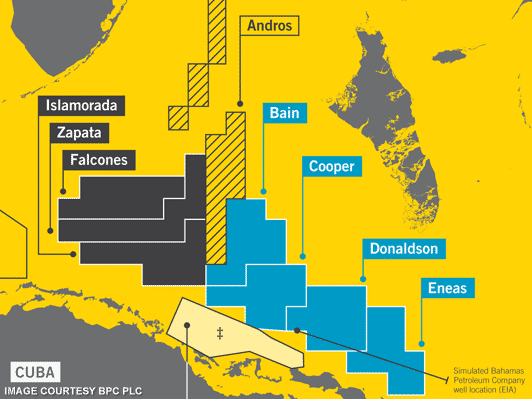

Bahamas Petroleum Co (LON:BPC) was granted licenses in 2007 to conduct offshore exploratory drilling for oil in areas covering roughly 16,000 sq km in the territorial waters and maritime Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of The Bahamas. Founded by Australian entrepreneur Alan Burns in 2005 and incorporated in the Isle of Man, BPC raised seed capital through a 2008 listing on the London Stock Exchange. The group holds 100 per cent interests through wholly owned subsidiaries in five exploration licenses granted by The Bahamas government, has joint applications for a further three licenses and sole applications for an additional two licenses.

Even with licenses granted, however, share prices have languished during the last year, as uncertainty lingered over when exploratory drilling could realistically commence. A moratorium on drilling by the previous government stalled development until an announcement by the incumbent administration in March this year that it would reverse its decision to hold a public referendum on offshore drilling paved the way for BPC to renew development efforts.

“We are not going to ask the electorate to vote on whether they want to develop an oil industry, if there is no oil to begin with,” Environment Minister Kenred Dorsett said in a statement released at the time. “Thus, we need to find out first, through exploration drilling, whether we do indeed have oil in commercially viable quantities.”

For BPC, which has already invested upward of $50 million in precursory investigations into potential oil reserves, it was understandably welcome news.

“We’ve done all the theoretical exploration work to the extent where the only thing we can do now is to drill. The announcement by the government means we can move on to the next stage,” says Simon Potter, BPC’s chief executive officer, who adds that the signs are positive for a substantial find. “We are always looking for the next big thing and we think that The Bahamas has that potential. It has many of the ingredients that we look for such as reservoir and seal rock, and adjacent oil producing fields. We have poured a lot of money into this project already and it looks better and better from a technical point of view.”

Funding operations

Having obtained the go ahead, the next step is to secure funding. “Having reduced the risk through our research, we are now looking to spread that risk with a partner,” says Potter, an industry veteran with 30 years oil, gas and mining sector experience, including 20 years with BP plc (LON:BP).

“Encouragingly, we have already received a couple of offers, but commercial negotiations have been constrained by the uncertainties of being able to drill. The clarification in March has made straight forward commercial conversations with partners a lot easier.”

Once the drilling starts, of course, costs get seriously ramped up. BPC intends to drill to 20,000 ft in the seabed around 80 miles south west of the nearest inhabited Bahamian island, Andros–around 170 miles from Nassau. It will be a 120-day well, costing approximately $1 million a day to operate. “It is important to get the right partners and put the right development plan in place. That is why, realistically, we are not aiming to start drilling until the latter half of 2014,” says Potter. “Not only do we want it to be safe, but also efficient. If you are sitting around for a day or two waiting on something or someone, then you are chewing up capital pretty quick.”

Moreover, this is no venture for the risk adverse. Potter says that despite all the money and man hours BPC has plowed into the project, there is still only a one in four or one in five chance of success. “That’s relatively low risk by international standards, but it still means there is a greater chance of finding nothing than finding something. Until you drill the well, you just don’t know.”

Economic impact

If found, the prize could be substantial, both for investors and the Bahamian economy. Based on the value of the rock structures and seismic readings, BPC is projecting lower estimates of reserves of around a billion barrels. To put that in perspective, international conventions define a field of a half a billion barrels as “giant.”

From the moment BPC sells its first barrel of oil, the government of The Bahamas receives 25 per cent. Taking a rough average of $80 a barrel, that equates to a $20 billion injection directly into the public coffers over the life of a billion-barrel oil field. The best part for the government is that it is straight off the top. The government has paid none of the development costs of exploration, extraction or transshipment and has not had to factor in cost escalation or unforeseen events. All costs up to that point have been borne by BPC and its investors.

Potter calculates that developing and operating the field will cost around $20-40 billion, and that’s as long as the actual size of the field found is commercial. “Whilst the headline rate for the government is 25 per cent of the income stream, after you have factored in the cost of construction, development, operation and maintenance it is closer to 50-50,” adds Potter. “The government has made none of the investment and takes none of the financial risk.”

Environmental issues

There is, however, attendant political risk, especially in light of the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, when an estimated 4.9 million barrels of oil was discharged from the Macondo Prospect into the Gulf of Mexico. Offshore drilling, particularly in a jurisdiction that has built an economy based on pristine waters and marine ecology, is a vote decider.

BPC is keen to point out that there are basic differences between the BP project and the proposed drilling site in The Bahamas. The subterranean strata, the water depth and reservoir pressure are all different. Tighter regulatory and operating standards have been introduced since the disaster and the US government has shown renewed confidence in the industry by issuing more than 300 approvals for drilling in the Gulf of Mexico in the last three years.

For its part, the Bahamian government is drafting new legislation that it says will enforce international standards and lower risk.

“The oil industry learns pretty quickly and the nature of the legislation that the government will put in place and the nature of the equipment that we have to have on the rig will mitigate the prospect of that kind of spill ever happening in The Bahamas,” says Potter. “On a number of fronts the risk [of a spill] is relatively low.”

Besides, Potter notes, The Bahamas is already exposed to considerable risk currently, but gaining none of the benefits. Although presently on hold, drilling has been conducted in the adjacent waters off Cuba in recent years; more than a billion barrels of oil travel through Bahamian channels every year, and Grand Bahama is home to the region’s biggest oil transshipment hub at BORCO.

“Between oil discovery and production, there will be six to seven years of planning and development. That gives us plenty of time to plan in terms of education and vocational training for Bahamians,” adds Potter. “All we can do is present the merits and put the risks in context.”

The government has pledged a public referendum before production can start if oil is found. So, as it stands, the Bahamian people will still ultimately decide the fate of the project.